Preventative Maintenance – Where Are You Now?

When it comes to preventative maintenance (PM), which scenario best describes your plant: Clipboards hanging from the side of machines for logging equipment failures and line downtime, or vendor-provided maintenance schedules? Both are actually a good start! But unfortunately, operator-collected data carries the intrinsic risk of bias and error, and vendor maintenance schedules can’t possibly correlate directly to a plant’s unique production cycles. The best way to create a PM schedule that minimizes downtime is to base it on your own historical data.

Put Your Machine Data to Work

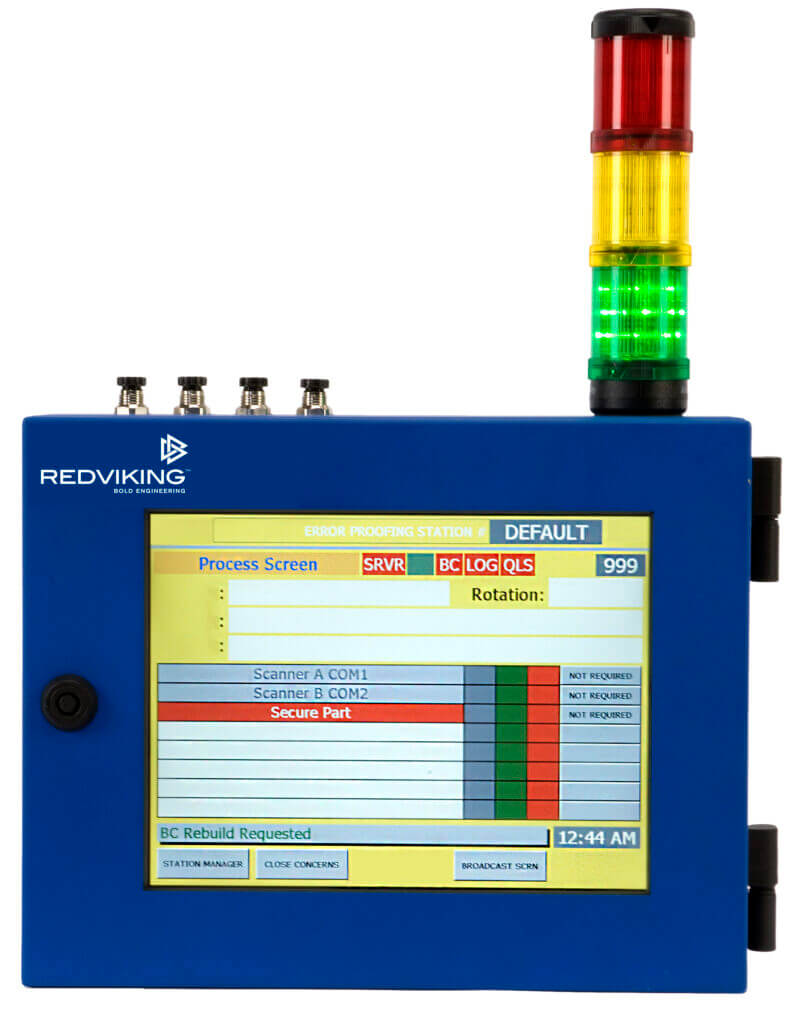

Manufacturers know they have the raw equipment data; they just need a way to capture it and convert it into useful equipment health monitoring information. A manufacturing execution system (MES) provides that vehicle. Rather than rely on a vendor-provided maintenance schedule or a manual log, an MES creates a PM program based on historical cycle counts. Data is collected through plant floor controls and incorporated into a database. Rules are then created based on actual tool and equipment wear patterns, and maintenance work orders are generated.

Stand-alone or Fully Integrated

An MES can be self-contained or customized around a plant’s existing software. For example, a global automaker uses real-time production counts and time in the cycling state to feed its off-the-shelf maintenance scheduling software. In the past, the company had to perform its most labor-intensive maintenance operations during shutdown periods. Equipment failed between shutdowns and downtime resulted. Today, the PM schedule for even its most complex machines is based on actual use and wear patterns, allowing production and maintenance schedules to work together to minimize downtime. In another example, a large engine manufacturer has a self-contained equipment health monitoring MES. Its rate of tool failure was creating unacceptable levels of downtime and scrap. A system was developed to collect usage data from each individual tool and define maximum tool life. A line-side human-machine interface (HMI) was provided to allow the tool’s anticipated life to be viewed by operators. Today, when a tool approaches 90 percent of its maximum expected life, the system alarms, notifying the operator and the maintenance staff. As a result, not only have downtime and scrap decreased, but the overall cost of tools is lower because purchasing can identify and buy the tools that last the longest.

Process Design and Management

Once equipment health monitoring systems are in place, an expanded MES can identify and prevent bottlenecks, guide overall process design and facilitate line changes. For example, a plant wanted to increase its line speed from 17 jobs per hour (JPH) to 23 JPH. The plant used its MES to understand operator cycle times by shift. One of its shifts had limited over cycles, while another shift had a much larger occurrence of over cycles. Was there a variation in training, or a lack of parts? Or, if both shifts were identical in those aspects, was there a process issue at fault? The MES allowed the industrial engineering team to determine whether an operator or process issue was the root cause, correct it and bring line speed up to the target of 23 JPH. Plants running multiple assembly lines can use data from one line to prevent problems in another. When an equipment issue is creating problems on Line A, maintenance staff can take action to prevent the issue from occurring on Line B. When a new process or machine is added to multiple lines, the MES can compare and contrast equipment health on each line to quickly head off problems across all lines. An effective MES equipment health monitoring system should increase uptime, reduce scrap and tool costs, and provide the foundation for a complete process management system.